MAPS

For more on the background to mapping as writing tools, see the training/resource page “writing for performance.”

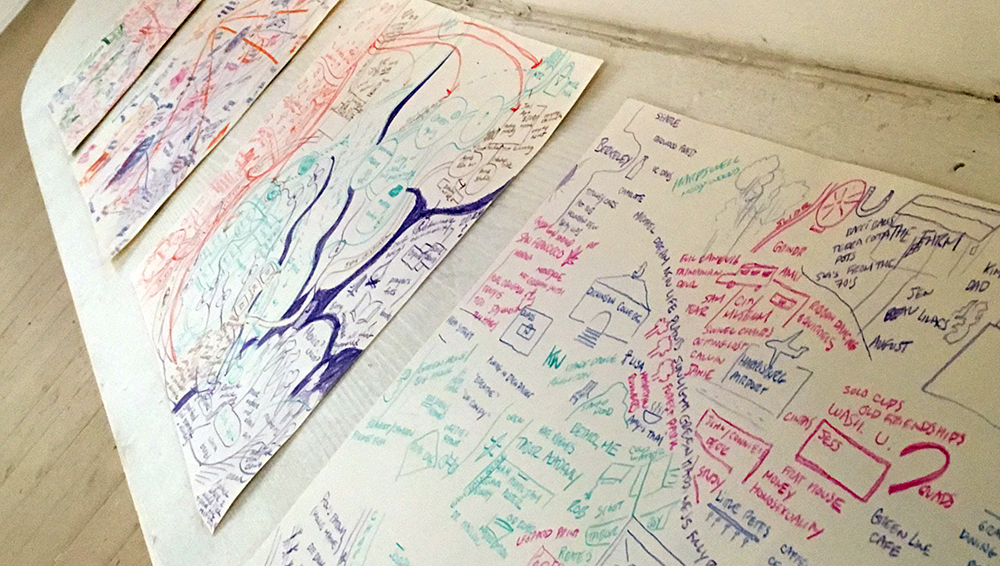

The first afternoon of our Hudson retreat was spent drawing maps that ended up becoming shared resources not just for writing, but for oral history interviews and later, our children’s stories.

On one large sheet of paper, each performer drew five overlapping maps, each with a different color pencil. We prepared by brainstorming a list of categories through which we could pull up specific details of our lives: scenes of education; scenes of relationship; brushes with death; kinds of kisses; beginnings/births; endings/death; transformation; moments of solitude; favorite clothes… Then each performer selected their own set and created a map using any combination of drawing or writing labels (most used both, icons and captions). So a layer of the map might have three or four instances of, say, a brush with death, and these were laid out on the page without regard to actual geography. As the maps filled up, things were recorded where there was available page space, so the relations of nearness between these details of our lives were dislodged from chronological or geographic fact.

Then I would lead question-prompts to populate that layer of the map: Who is in that place? What is moving very slowly in that place? What is moving very fast in that place? What is something you didn’t know about when you were in that place? What is far away from that place? What would never be allowed in that place? What industries supply that place? What did you gain? Draw something there, that doesn’t actually belong to that place. If there was a patron saint of this place, what saint could that be? What is at stake for you in remembering that place? What is the currency in that place? What is in the next region over?

In further layers, I asked mappers to link sites in their maps with vehicles or pathways, or obstruct their connections with an object or natural feature. I would have people ring the area of their site: What else is there? Where were you before you came to that place? And so on through a proliferation of prompts (more than could be caught by any one hand), so that these intense, marked moments were embedded in a field of detail.

We used the maps as anchors in oral history interviews, asking the narrators questions about things in their maps.

Later, we wrote prose poems that performed a classical ekphrasis (an art history term, meaning, a literary description of a work of art) of our own and each other’s maps, treating the map as the object of description (as opposed to using the map as a key to a life story). These became the text used as both script and choreographic prompt in Color Bubbles.